"James Mathers' Bohemian Rhapsody"

by Pablo Capra, November 2003

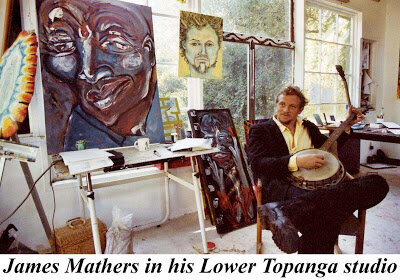

Photos by Katie Dalsemer

Growing up in Topanga Canyon, artist James Mathers was baby-sat by young women he described as “fantastic hippie girls” who would hitch-hike with him down to the beach, and then go to the Rodeo Grounds “to hang out in hot tubs with surfers and actors.”

Thus, Mathers became a part of the Lower Topanga community.

At 17, Mathers moved to New York to embark on his “glorious and disastrous” painting career. In the ’80s, he showed paintings in the Lower East Side, then moved to Europe where his paintings were exhibited by galleries in Switzerland and Italy. He spent a year painting in Indonesia, and four years in Ireland. In Ireland, he ran an anarchist bookstore called Garden of Delight and started writing screenplays. He sold one called “Crushproof,” about a subculture of tough young kids who rode horses through the streets of Dublin.

But during his travels, he always kept a house, trailer or art studio in Lower Topanga—”the last bit of what Topanga felt like when I was growing up,” says Mathers.

According to Mathers, the bohemian lifestyle of Lower Topanga performs a “vital function” in our society.

“If the idlers, poets and headcases didn’t go down to the beach at night to give thanks to the ocean and the sky, who would?” he asks.

Mathers’ unconventional lifestyle is evident in his appearance. His baby-thin hair is never brushed, his face is unshaven, and he wears cheap suits and black combat boots, a vestige from his punk days.

He currently shares an Airstream trailer and an art studio in the Rodeo Grounds with his girlfriend, fellow artist Daisy Duck McCrackin.

An actress, painter and songwriter, McCrackin was named after a cartoon character by her guru Adi Da Samraj when she was born on a commune in Northern California.

Mathers and McCrackin are two of about 40 people who are trying to hold out in Lower Topanga and preserve what is left of their community. Their trailer is surrounded by three boarded up houses and a vacant lot where a fourth house was bulldozed in May.

Mathers says that living in a disappearing community makes him more aware of the temporality of life and gives him a feeling of urgency to document it. In a recent comic strip, he depicts his life in Lower Topanga through the magical rituals he performs in praise of arundo, his frustrations about the demise of his neighborhood, and his relationship with McCrackin.

“Yes, I do burn money and am in contact with the fairies,” says Mathers.

He says he feels connected to the arundo canebrakes in Lower Topanga.

“They are implacable, assertive and the State wants to have them removed.”

He has learned a valuable lesson from arundo, in life and art—”to just endure.”

He is glad that the state Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority’s project to use herbicides on the arundo in Lower Topanga was defeated.

“It’s remarkable that the people who are being kicked out of Lower Topanga are actually the ones who are preserving the land, and not State Parks!

“We’re serving our purpose down here.”

In 1999, Mathers wrote and directed a film, “King of L.A.,” about a poetic homeless man living in downtown L.A. This year, he wrote and illustrated a children’s book called “The Children’s Guide to Astral Projection,” which he is trying to get published. The book teaches children how to have out-of-body experiences and prepares them for encounters with other-dimensional creatures on the astral plane.

“It’s the book I would like to have had when I was a kid,” says Mathers.

Mathers will be emceeing a reading of “Idlers of the Bamboo Grove: Poetry from Lower Topanga Canyon” on Sunday, November 9, at 4 p.m. at Beyond Baroque. Mathers illustrated the book, and he and McCrackin contributed poems to the collection of writings by residents of Lower Topanga.